Article by Lynda La Rocca

Local Artist – August 2002 – Colorado Central Magazine

The light emanating from Bill Harrington’s paintings does more than bathe his work in a rich, mellow glow. It also illuminates Leadville’s equally colorful mining heritage.

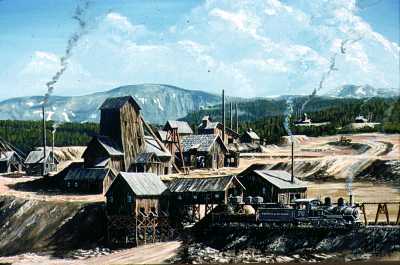

For more than 20 years, this third-generation Leadville native has helped preserve scenes of contemporary and frontier-era high country mines, mills, and railroads in meticulous, historically accurate detail.

“My art reflects who I am, where I live, and how I was raised,” explains Harrington, sitting at his kitchen table with wife Marcia, daughter Kathleen, and son Johnny. “There’s so much history and natural beauty here. When you live in the middle of all this, how can you not paint what’s around you?”

A miner for 33 years, Harrington paints in his “spare time” after his regular job doing reclamation work at the Climax Molybdenum Company mine site atop Frémont Pass. He credits his father John and his Leadville high school art teacher Sylvia Stoner with instilling his lifelong passion for art.

“I took a correspondence course, too,” Harrington adds with characteristic modesty. “Then I just went out on my own and did my own thing.”

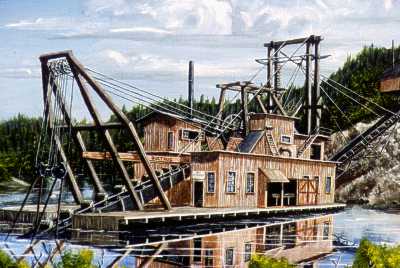

That “thing” includes roaming the hills of 19th-century mining districts in and around Leadville to photograph, sketch, and record every detail of the ore chutes, headframes, sluices, smokestacks, and gold dredges that appear in his mining-themed acrylic paintings and his pen-and-ink and graphite drawings.

Harrington, 51, also depicts Lake County’s rugged natural beauty in landscape paintings of mountain meadows and forests, rushing streams, and snow-covered peaks. And he travels around Colorado seeking examples of another favorite subject: historic steam locomotives. But no matter what he’s portraying, accuracy is always paramount.

“I’ll paint every single bolt on a steam engine, no matter how long it takes,” Harrington says cheerfully.

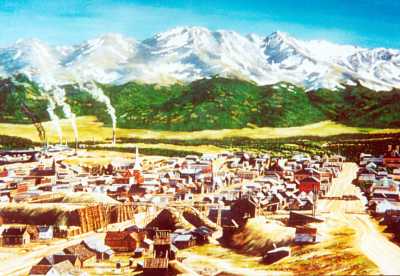

And he’ll keep working on a piece until he gets it just right. Harrington once painted a Leadville scene in which the rooftops along East Sixth Street were tilted at the wrong angle. When he realized his error, “I went back and redid every single rooftop until they all looked the way they do in ‘real’ life.”

It took two years and almost 400 hours to complete that panorama, which Harrington named after journalist Carlyle Channing Davis’ 1916 declaration, “There Has Been But One Leadville and There Will Never Be Another.”

“I gave it that title because I’ll never spend so much time doing another painting like it again,” Harrington jokes.

The crisp, precise lines that distinguish Harrington’s work reflect a perfectionist who has never been completely satisfied with any of the 100-plus paintings he has thus far produced.

“I always like some part of each one, but I also always feel that I could have made another part better,” Harrington explains.

“Whenever I start a new painting, I say, ‘I’m going to do it this time. I’m going to paint the perfect painting,'” he grins. “But I still haven’t.”

Not that anyone is complaining. Harrington’s work, much of which is produced on commission for private collectors throughout the western United States and England, is on permanent display at Leadville’s National Mining Hall of Fame & Museum. Prints of his drawings are also available at The Rock Hut on Harrison Avenue.

And his work is featured on the cover of the book Colorado Gold by Twin Lakes author Stephen M. Voynick. In this painting, Harrington puts aside his insistence on realism to conjure an imaginary scene of two frontier miners panning for gold and working a rocker (a device used to manually wash gold from gravel) in the Colorado high country.

When it comes to existing structures, however, Harrington’s favorite is the Wolftone Mine off East Fifth Street on Leadville’s “Route of the Silver Kings” historic mine district tour. The Wolftone, which began operations in the 1880s as a gold-silver-lead-zinc producer, is remembered as the site of an underground banquet for 250 guests, hosted by mine owners in 1910 to celebrate a particularly impressive ore discovery. This mine has left its mark on all of Harrington’s work; its long, slender, coal-furnace stacks inspired him to create his stylized signature.

Harrington’s penchant for pure, vivid color is evident in stunning orange and pink sunsets, achingly blue skies, bright yellow-gold aspen stands, and deep green subalpine forests. It therefore comes as something of a shock to learn that this artist is color-blind.

“As a child, I’d paint green tree trunks with brown leaves,” he says. “Blue and purple look the same to me; so do red and brown. Now when I see a beautiful sunset, I’ll ask my kids, ‘What color is that?'”

Initially, Harrington’s family helped him select precise shades. As his work progressed, however, he developed his own elaborate system of charts for mixing colors and written formulas for blending to achieve specific hues. He also learned to gauge color values by determining degrees of light and dark.

Since the deaths of his parents, John and Staffie, in the 1990s, Harrington has frequently incorporated tiny versions of their initials into his paintings. Some of his mining-themed work also features a similar kind of tribute.

“I used to put, ‘Dedicated to the Miners’ on the backs of my paintings,” Harrington explains. “I’ve always tried to capture the hard work that goes into mining. It’s tough, and tough people do it.”

But Harrington portrays more than the individuals who made Leadville the frontier West’s wildest, roughest, richest silver camp and who continued to sustain the Cloud City’s identity as a mining town long after many similar settlements had been abandoned.

“I try to capture the spirit of Leadville, what Leadville used to be, because that’s disappearing and it may not be remembered otherwise,” he explains.

“I’m saying, ‘This is what it looked like. This is what Leadville was.’ I don’t want people to ever forget.”

That’s not likely, as long as Bill Harrington maintains his passion for painting scenes of Leadville and its rip-roaring mining legacy.

Lynda La Rocca writes from Twin Lakes.