Essay by Ed Quillen

History – February 2007 – Colorado Central Magazine

FOR MUCH OF THE PAST YEAR, I have followed Zebulon Montgomery Pike across the Great Plains and around Colorado — reading his journal, writing a monthly summary for this magazine, attending a few bicentennial events.

And it strikes me that Pike’s job is still unfinished two centuries later.

Pike was sent out to establish the boundary between the United States and the land that would become Mexico. But that is a border — at least in a cultural and economic sense — which still remains in flux today, as we are reminded with every raid by the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement service.

If the boundary issue can be said to start with any single event, it might well be a 1682 voyage by René Robert Cavalier, Sieur de La Salle. He floated down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico, and claimed the great river, and all of the territory it drained, for France. To honor King Louis XIV of France, he named the land Louisiana.

The eastern side of the river went to England for its victory in the French and Indian War (1756-63, and known as the Seven Years’ War in Europe).

The west side went to Spain, Britain’s ally in that war. Spain also held Florida and had claims along the Gulf Coast, and of course Mexico was a Spanish colony.

An expanding America put pressure on Spain, and one result was the 1795 Treaty of San Lorenzo del Escorial. Spain would get to keep Florida, but would give up its other claims east of the Mississippi and guarantee Americans free navigation along the Mississippi. Meanwhile, Americans kept pushing westward, primarily into Texas.

Thomas Jefferson, who became president in 1801, saw Spain as a weak empire that posed no threat to the United States if push came to shove. However, off in Europe in 1802, Napoleon maneuvered Spain into ceding control of Louisiana back to France, and that worried Jefferson. For one thing, no treaty with France guaranteed that the Americans would have the right to use the Mississippi River, and settlers in Kentucky and Ohio relied on that river to get their goods to New Orleans and to world markets. For another, France was a real military power; Spain wasn’t.

So Jefferson offered to buy New Orleans for $7.5 million. Napoleon countered by offering all of Louisiana Territory “as France possessed it” for $15 million. Thus the “Louisiana Purchase” of 1803 was made.

There were no accurate maps. It hadn’t been surveyed, and there was no formal legal description. “As France possessed it” didn’t mean much. France had not built roads and forts, nor had it established settlements. There were just a few traders who left a few French place names like Platte, La Porte, and Cache la Poudre.

Jefferson dispatched two expeditions to help establish boundaries and solidify American claims. One was the famous Lewis and Clark Corps of Discovery up the Missouri and down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean. The other is quite obscure — the 1806 Curtis-Freeman Expedition that was supposed to ascend the Red River and descend the Arkansas. It was halted by a Spanish force just inside what is now Texas.

WHY THE CONCERN with the Red River? The Red is the last significant stream to flow into the Mississippi from the west. If you have a claim to the drainage of the Mississippi, then charting the drainage of the Red will establish the southwest boundary. Today the Red forms much of the boundary between Texas and Oklahoma.

Pike was part of this effort to establish the boundary of Louisiana. His orders came not from President Jefferson, but from Gen. James Wilkinson, commanding general of the U.S. Army. Wilkinson had schemed with Aaron Burr, vice-president under Jefferson in his first term, to send a private army into the West, perhaps to set up their own empire on this side of the Mississippi. Wilkinson was also on the payroll of Spain, and it’s difficult even now to figure out just where his loyalties lay.

Pike led two expeditions to determine the limits of Louisiana. The first was in 1805-06, when he went north from St. Louis to find the source of the Mississippi and to inform British traders that they were on American soil. He missed the actual source, Lake Itasca in Minnesota, by a few miles, and instead put it at Cass Lake.

PIKE’S SECOND EXPEDITION brought him to Colorado, where his orders were to ascend the Arkansas to its headwaters, then descend the Red. His findings were supposed to determine the boundaries of Louisiana.

Pike never found the Red, though. Logic led him to believe that the Red had to start in the Rocky Mountains, not the panhandle of Texas (as it does), and rumors of the era had the Red starting somewhere near Santa Fé. The territory was pretty much a mystery to Americans, though, since Spain didn’t let intruders leave the territory. While in Santa Fé, Pike encountered James Purcell (Pursley to Pike), an American trader who was allowed to make his living as a carpenter, but could not get permission to leave.

In the broad sweep of American history, we can see the Pike expedition as part of a series of border incidents between Spain and the United States. Even at the time, Americans were pushing across the Sabine River into Texas, and a dozen years later, in 1818, Gen. Andrew Jackson invaded Florida and seized Pensacola.

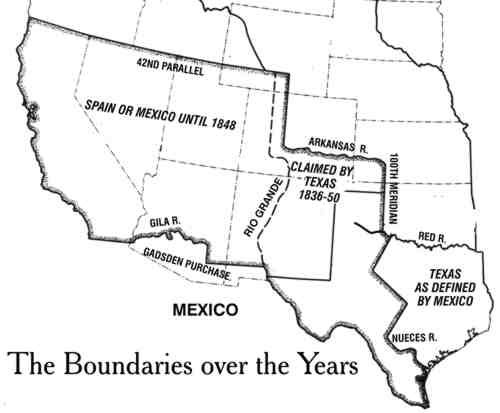

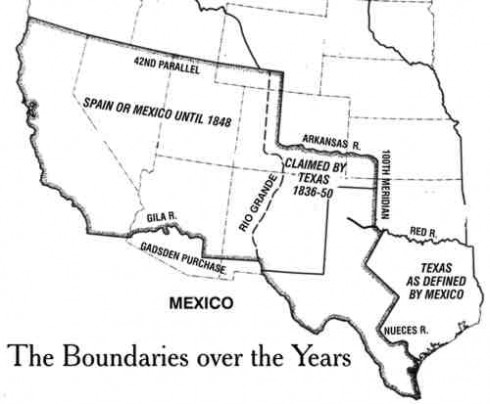

The vague boundary of Louisiana had to be settled either by negotiation or by force, and the United States and Spain took the peaceful course with the Transcontinental Treaty of 1819, which was negotiated by U.S. Secretary of State John Quincy Adams and Luis de Onís, the Spanish ambassador to the United States. In it, Spain gave up Florida; the United States “forever” renounced any claim to Texas; and a formal boundary was drawn between American Louisiana and the domain of Spain. From the 100th Meridian near present Dodge City, Kansas, west and north to its source, the Arkansas River became the boundary.

When Mexico became independent of Spain in 1821, it inherited the northern boundaries.

But in 1836, Texas seceded from Mexico, and claimed the Rio Grande as its western boundary, all the way up from El Paso to Creede and beyond. Up here, the Arkansas remained its border with the United States, up to its source. But past that point, Texas stretched even further north. Draw lines up from the tops of the Arkansas and the Rio Grande, to the 42nd Parallel in Wyoming, and you get one long, narrow strip through Colorado and beyond.

Not that the Republic of Texas ever did much up here. But in 1841 it did dispatch soldiers to take Santa Fé on the grounds that everything east of the Rio Grande belonged to Texas. Before the invaders could cool their horses, however, the Mexican Army defeated and captured them.

IN 1844 THE Republic of Texas joined the United States (even though in 1819 the United States had forever renounced any claim to Texas), precipitating the Mexican War of 1846-48.

One issue at the start of that war was the boundary between Texas and Mexico. Mexico recognized the Nueces River as the western boundary of Texas; but Texans claimed everything to the Rio Grande. American soldiers marched into the disputed area, and were fired upon, thereby providing a reason to go to war.

Abraham Lincoln, then a congressman from Illinois who opposed the war, made a pest of himself by asking where the “spot” was that first blood was shed. Thus his political opponents began calling him “spotty Lincoln.”

Ulysses S. Grant, who fought with distinction in that war, later wrote that “Mexico showing no willingness to come to the Nueces to drive the invaders from her soil, it became necessary for the ‘invaders’ to approach to within a convenient distance to be struck. Accordingly, preparations were begun for moving the army to the Rio Grande.”

After the United States won the war, and got the rest of Colorado, along with New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Nevada, and California, there remained the Texas claims up here. That was settled in the Compromise of 1850. The United States agreed to pay off some debts run up by the Republic of Texas, and Texas agreed to scale back its claims to its present borders.

But the boundary between the United States of America and Los Estados del Mexico was still not settled.

Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce in 1853, wanted a southern transcontinental railroad route to tie the new territory in the West to his beloved South. The best route lay south of the Gila River, land that was still in Mexico. So Pierce sent James Gadsden to Mexico to buy some territory — the southern quarter of modern Arizona and a part of New Mexico.

Pierce and Davis wanted to buy a lot more, including Baja California, but Mexico wasn’t willing to deal, and there was American opposition from anti-slavery groups who didn’t want more potential slave territory in the United States.

The formal political boundary has stayed pretty much the same ever since that treaty was ratified in 1854, with some minor adjustments caused by changes in the course of the Rio Grande after floods. So the job Pike started in 1806 — to determine the border between the United States and Mexico — is presumably done, and has been done for 153 years.

YET THERE STILL isn’t an end to this business of securing a border. Just about every day, we read stories about “undocumented workers” or “illegal immigrants” in the United States, as well as of plans to build a 700-mile fence along the border, and of some politicians proclaiming “no amnesty for law-breakers” while our President promotes a “guest-worker” program with a “path to citizenship.”

Actually, I think George Walker Bush is on the right track there, hard as it is for me to say anything good about him.

I try to imagine other solutions (immense walls, mass roundups with deportations, employer enforcement ) and nothing seems realistic. Just as it was in Pike’s time, the border between the United States and the Spanish-speaking realm in the southwest remains vague and porous. The only real difference seems to be that back then, it was the authorities in Mexico who were worried about border-jumping foreigners — like Pike and Purcell.

— Ed Quillen